Blog Layout

Material Requirements Planning

Don Agostino • Jun 17, 2020

Material Requirements Planning

Not a day goes by in the life of a manufacturing professional that we don’t hear the term Material Requirements Planning, or its more common abbreviation MRP. We are all familiar with the term, and what it means, but how well do we really understand the inner workings of the tool? Before MRP, most manufacturing companies relied on what was referred to as the “order launch and expedite” system, whereby work orders were released to the floor based on upcoming shipments and expediters worked their magic to get the orders done on time. This led to great inefficiencies in material procurement and resource usage, but there didn’t seem to be any other choice.

The Origins of MRP

No one knows for sure who first put the words together but one of the original proponents of Material Requirements Planning was Dr. Joseph Orlicky, who wrote the first book on MRP while working for the IBM Corporation. Many people had been using the concepts but nobody pulled everything together in an easy to read publication. So, what exactly is MRP?

You’ve heard the jokes: “More Reams of Paper”, referring to the massive computer output of the mainframe devices in use back in the 1060s and 1970s. Or how about “Marketing Runs the Place”, expressing the frustrations of the production managers trying to fulfill the ambitious goals of their sales counterparts. But was MRP that “new” or “radical”? And why the shroud of mystery? After all, it’s an easy to understand concept once you get “under the covers”. Most of the tools were already in place, such as Bills of Material, inventory management, sales orders, etc. The trick, of course, was to pull everything together into a coherent whole.

The main problem was the fact that people were focused on the wrong objectives. Prior to MRP the main focus of inventory management was stock replenishment, which essentially specified a desired inventory level for each product and techniques such as reorder points and Economic Order Quantities (EOQ) to ensure that the inventory was kept at the desired level. This level was dictated by the “service level”, namely the ability to meet demand and avoid a stockout.

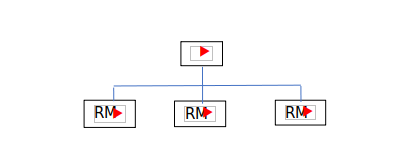

These required adherence to unrealistic assumptions: 1) that demand for the products being built and sold was steady and predictable, and 2) the supply of raw materials was likewise known with certainty. These techniques were taught in universities and were considered the “state of the art”. It was not necessary to use a computer; these calculations were simple and could be done on a slide rule or manual calculator. Demand was based on a sales forecast, and the various inventory control techniques insured that there were sufficient materials on hand to build the products. But one piece was missing, namely that of “dependent” demand. Dependent demand states that the demand for a part is based on the demand for another part, as illustrated in the diagram below:

Bills of Material, as depicted above, were already in widespread use as an engineering or design tool, but nobody thought of them as a Planning tool. It’s such a simple concept but it was a breakthrough at the time. The “breakthrough” was not the dependency, which was obvious, but the notion that the demand for the raw materials could be computed based on the production schedule for the finished product. There was no longer a need to maintain a specified stock level of each component part, only to make sure that the materials were available when needed.

MRP Logic

Basically, MRP is designed to answer four questions:

- What are we going to build?

- What materials do we need to build the items?

- What materials do we have?

- What do we need and when do we need it?

The term “when needed” brings up a second concept, that of “time phasing” or the process of insuring the materials are available when production begins on the finished goods. Thus, there is an “order by” date for the purchased components based on the “need by date” of the component and its purchase lead time, plus any allowances for receiving inspection, kitting, or material certification processes. These calculations required a computer, as the demand for the finished goods was typically not “known and steady”, which was one of the central tenets of the EOQ model discussed above.

Now that the notion of a “desired” inventory level was dispelled, it became obvious that the desired stock level of each part is zero. There is no need to carry inventory for a Dependent Demand item unless it will be used in production. This led to the Basic MRP Model.

Let’s assume:

Forecasted sales for FG of 100 per period for the next 8 periods

On hand inventory of RM1 of 200 units

Each unit of FG requires one unit of RM1

| Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales Forecast | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Requirements | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Scheduled Receipt | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Projected On Hand | 100 | 0 | -100 | -200 | -300 | -400 | -500 | -600 |

| Net Requirements | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

OK, nothing new here. We all know how this works. Starting with 200 units of RM1 on hand, we would need 100 units per period starting in period 3. So far, we have answered the four questions listed above, but how to satisfy this demand? Let’s add another row to the table. Assume a two-period lead time for part RM1:

| Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Net Requirements | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Order Release | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

With a “Lot For Lot” order policy, we would need to order 100 units of RM1 in each of the first six periods of our planning horizon. Now let’s add some more information, such as open purchase orders for RM1:

| Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales Forecast | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Requirements | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Scheduled Receipt | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Project on Hand | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | -100 | -200 |

| Net Requirements | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Order Release | 200 |

This assumes a purchase order quantity of 200 units, or a “Fixed Order Quantity” policy. Does the above look familiar? It should, this is the Time Phased Inquiry in Epicor showing supply and demand. This demonstrates the fundamental objective of MRP, which is to keep supply and demand in balance. Remember that MRP wants to keep inventory at zero, or as close to it as possible, based on supply and demand. To that end, MRP may ask us to do things that may not make sense. For example, look at what happens if the demand in period 3 changes to 150 units:

| Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales Forecast | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Requirements | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Scheduled Receipt | 0 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 200 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Project on Hand | 100 | 0 | 50 | -50 | 50 | -50 | -150 | -250 |

| Net Requirements | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50 | 0 | 50 | 100 | 100 |

| Order Release | 200 |

Please note that MRP will plan based on the greater of sales orders or sales forecast in a given period. In period 3 we see that a surge of orders pushed demand above the 100 units forecasted.

MRP will respond to a net requirement in one of two ways:

- Reschedule an open order, or

- Create a new planned order.

In this case MRP will generate three suggestions:

- Move the purchase order receipt from period 5 to period 4

- Change the quantity of the expedited purchase order to 50

- Create a purchase order in period 3 for 200

Here is the updated material plan:

| Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales Forecast | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Requirements | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Scheduled Receipt | 0 | 0 | 200 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Project on Hand | 100 | 0 | 100 | 0 | -100 | -200 | -300 | -400 |

| Net Requirements | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Order Release | 200 | 200 |

Remember that MRP wants to keep inventory at zero, and since the net requirement in period 4 is 50 units then that’s what MRP will tell us to do. This leads to the plethora of suggestions that MRP generates. MRP will always reschedule an open order before suggesting a new one, based on the (usually correct) assumption that our supplier will not accept a new order ahead of an existing order. And, unless we say otherwise, MRP will also tell us to reduce the order quantity to the net requirement of the period. We would need to lock the quantity on the purchase order release to prevent this from happening.

What affects MRP Processing?

Among other things, this would be the Order Policy – how much to order at one time. These come in different forms:

- Lot for Lot, also called Discrete, where each planned order is in the exact amount needed.

- Fixed, where the order quantity is the same for each planned order.

- Min / Max / Multiple, where the order quantity is no less than the stated minimum, no more than the stated maximum, and always a multiple of a given quantity. Note that this order policy, and the previous, can result in multiple orders in the same time period.

- Days of Supply, where the order quantity is computed to cover the net requirements for a given period of time.

The choice of order policy for a given item is the result of several factors:

- Minimum order quantity (or amount) required by the supplier.

- A trade-off between the cost of placing the order and the cost of carrying the inventory. Note that this applies to manufactured components as well if we substitute Setup cost for the cost of placing the purchase order.

- Storage and material handling constraints.

- Spoilage and / or obsolescence concerns.

Another factor that affects MRP planning and suggestions is the Reorder Point, which is the stock level that triggers MRP to generate a replenishment order. In many ways, the reorder point is a leftover from the EOQ concept introduced above.

It specifies when an order must be placed with a supplier, or when a work order needs to be released to the shop floor. It consists of two parts:

- Minimum On Hand, which is the expected demand over the replenishment lead time, and

- Safety Stock, the amount held to compensate for variations in the lead time demand or duration.

In most MRP computer systems, the above will generate messages when the projected available stock goes below safety stock and again when it goes below the minimum, and generate planned orders to replenish stock. Basically, the reorder point is another level of demand above any sales orders and / or sales forecasts.

One thing that people often ignore which has an impact on MRP is scrap, both at the material and assembly level. MRP takes planned scrap into consideration, and will increase the manufacturing rate or material usage accordingly. Actual scrap is a different story, as unplanned scrap will result in a shortage of a component part or end item with the consequence of missing a delivery or having to release more material to the shop and rush the items through the production process. MRP must be made aware of the unplanned shortage so it can generate the proper messages to issue more material to a work order or issue more for future orders.

Last, the impact of lead times on MRP cannot be underestimated. MRP to a great extent relies on forecasts, of both demand and supply, and forecasts become less reliable farther into the future. While a two week lead time would not present a problem, what if the lead time is in excess of 26 weeks? This author worked with a manufacturer who was quoted a lead time of 75 weeks for a critical part, making a reliable delivery date for the end item virtually impossible. Worse, MRP uses a planned lead time, the actual lead time can be much different. The actual lead time for a purchased part depends a great deal on the importance of the customer to the supplier, while the actual lead time for a manufactured component depends on the rank of the expediter (do some of your expediters hold the title of Vice President?) It may seem OK if the actual lead time is less than the planned lead time, but that simply means that parts are available that have no immediate use and that other parts may have been sidelined to make way for them. Controlling lead times is no easy task but it is important to the proper workings of MRP.

MRP Output

Revisiting the four questions posed above, MRP provides a list of planned orders and suggestions for changes to open orders; basically to expedite, postpone, increase, or decrease an open order. If there is no demand for an open order, MRP will issue a cancel message. Implicit in these messages is the relative priority of each open order, not only what is needed but when. The main output of MRP is a list of what to make and buy, with the priority specified in the start and due dates for a work order or the order by and due dates of a purchase order. The beauty of MRP lies in its simplicity and its ability to respond instantaneously to changes in supply and demand.

Share

Tweet

Share

Mail

By Don Agostino

•

17 Jun, 2020

Producing and shipping high quality products at a reasonable price is the only way a manufacturer can remain in business. Gone are the days of “good enough” or “we compete on price, not quality”, manufacturers are being held to increasingly higher standards of quality by their competitors. Much of the credit for this goes to W. Edwards Deming, often regarded as the “father of Statistical Quality Control” based mainly on his early work in postwar Japan and who was widely regarded as a hero in Japan for his emphasis on statistics as a tool for improving quality in manufacturing. Statistical Quality Control (SQC) and Statistical Process Control (SPC) are the lifeblood of a manufacturing company that seeks to measure and capture data about their products and to monitor the production process to ensure high quality standards.

By Don Agostino

•

17 Jun, 2020

By now most, if not all, of you have heard of the Epicor Product Configurator and some of you may be very familiar with it. For those of you who are not that familiar with the Configurator here is a brief list of things that it can do: Automate the part configuration, engineering, or quoting process. This is crucial during the sales process to ensure the customers get what they need. Generate “intelligent” part numbers and descriptions. These can be catalog part numbers or “one off” parts created for a single quote or sales order. Generate a Bill of Material and Routing to assist in developing product costs. Prevent invalid configurations and combinations of options. The Configurator does this by capturing the knowledge of your engineering and design staff and placing it into the Epicor database, and then applying that knowledge during the sales process.

By Don Agostino

•

17 Jun, 2020

Scheduling of work orders through a factory is an indispensable part of managing a production facility, yet it is typically the last module of any ERP system that is implemented. The reason why this is true may surprise you, although it’s really not at all surprising. Basically, even though everyone understands the concept of scheduling, applying this concept in a production environment is very difficult. There are all kinds of reasons for this, but perhaps the most important is that people don’t understand what a scheduling module is supposed to do. There are the usual problems: suppliers don’t deliver on time, customers change their delivery dates, excess scrap, and so forth; but I have seen over time that many people do not have a good understanding of job scheduling. Of course, this knowledge will not automatically transform your shop floor into a model of efficiency, but it will at least give you the information you need to make informed decisions.

All Rights Reserved | Carlsbad Group

© 2024